Mapping Migration and Describing a crisis

What do you do with over one million non-EU migrants trying to enter the countries of the European Union? Whilst this number is relatively modest (two million migrants entered Turkey during 2015, for example), the scale of the challenge facing the member states of the EU is nevertheless real. The challenge of the numbers has far-right extremists baying for blood whilst the voices of the political left and the moderate centre lack the populist conviction that others are all too happy to peddle.

Consequently, much of the current debate about European migration policy resembles a game of political ping-pong with claim and counter-claim advanced, argued, and entrenched. The debate is not helped by a general lack of reasonably accurate statistics.

In 2008, I co-authored a unique book featuring the statistical and demographic investigation of the phenomenon of migration in Europe (Mapping Migration, Mapping Churches Responses: Europe Study). Our second revised and updated edition, published late 2015, demonstrates that the situation has changed almost unrecognisably. The challenge for any commentator or author writing about refugees, asylum, and migration in Europe is that the most recent data available is normally, at best, about 18 months old. Given that the current migrant challenge facing the EU only gained momentum during 2015, none of the statistical agencies (national and EU-wide) has access to current data. In any case, much of the official data relates to asylum applications (and decisions) and/or ‘managed migration’, and what can be observed at the current hotspots in Europe cannot be described as ‘managed’.

Reliable and credible statistics informing the current ‘refugee crisis’ in Europe are simply not available. Estimates exist, of course, and the most accurate suggest that just over one million migrants entered the EU during 2015. The accelerating challenge underlined the European Commission’s inability to predict, let alone manage, the highest numbers of non-EU migrants in the history of the EU. In September 2015, the EU began efforts to redistribute 120,000 non-EU migrants from Hungary, Turkey and Italy to other EU countries – just 12-15% of the estimated numbers of migrants entering the EU in 2015. Accurate prediction requires accurate statistical forecasting and there have been few oracles available to the EU.

Until more accurate statistics are available, we are reliant on narratives of migration and of personal encounter by Europeans with migrants and refugees. This is not necessarily or always second best. In the second edition of Mapping Migration, Mapping Churches’ Responses, we turn to migrant accounts of experiencing integration, belonging, and community in the churches of Europe. In this edition of VISTA, we have also taken the decision that our research approach to the current migrant situation in Europe is best ‘captured’ in a series of personal ‘snapshots’.

Of course, statistical research and anecdotal research are both involved in describing the same human experiences, the same overwhelming human needs. Whether numbers or sentences are used to describe them, the same rapidly changing currents and trends are apparent. In both instances one wonders whether the churches could do more. Could we, even I, do more? In this respect, the reporting of statistical data can actually increase the feelings of being overwhelmed. None of us is really able to do anything with the reporting by the EU’s Vice President in January 2016 that there were still 2-3,000 people arriving per day in Greece. Throughout 2015, deaths of migrants at sea rose from 500 per month to 2,500 per month by August. This latter fact alone prompted the EU to adopt its European Agenda on Migration in May 2015, in which measures were outlined to develop migration strategies focused on relocation, resettlement, counter-smuggling measures, fingerprinting guidelines, improving the EU’s Blue Card entry scheme for skilled migrants, and increasing resources for Triton, the EU’s border control measures.

Whilst there are many followers of Jesus serving Him in the debating chambers and committee rooms of Europe, most of VISTA’s readers are faced simply with the question of what to do when a refugee asks for the use of a mobile phone to make a call to a relative already living in Europe, or when he asks for an overcoat, a sleeping bag, some food, a bus fare. Is ‘Non!’ or ‘Nein!’ really a Christ-like response to such requests?

I first reported findings from the revised and updated edition of Mapping Migration to a gathering of church experts, gathered in Sweden during June 2014. On my return flight to Sydney, via Beijing, I met a diplomat from the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. On learning my reason for being in Sweden, he asked with some bemusement why the European churches were interested in migration. I replied simply that, since my work on the 2008 edition, it was clear that the churches of Europe are the most consistently and widely spread collectives of people who generally respond positively to the presence of migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers.

It’s also clear, from the many stories of such committed Christian engagement featured in this edition of VISTA, that this is still true. We also discovered it in our research for Mapping Migration. For example, a young Pentecostal male from Central Africa, living in France, told us ‘When I arrived here, I was immediately surrounded, integrated, and encouraged by the pastor as if he knew that I could bring something to the church.’

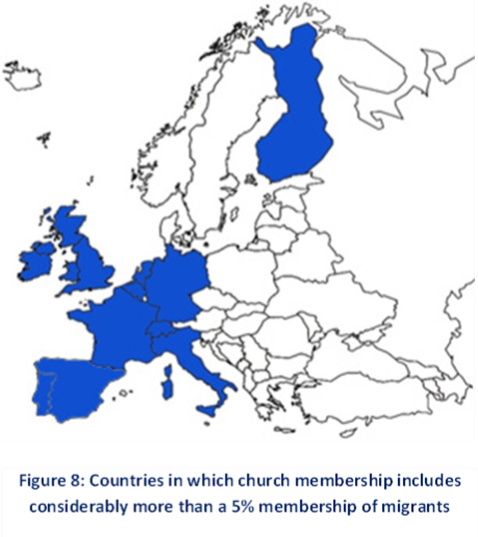

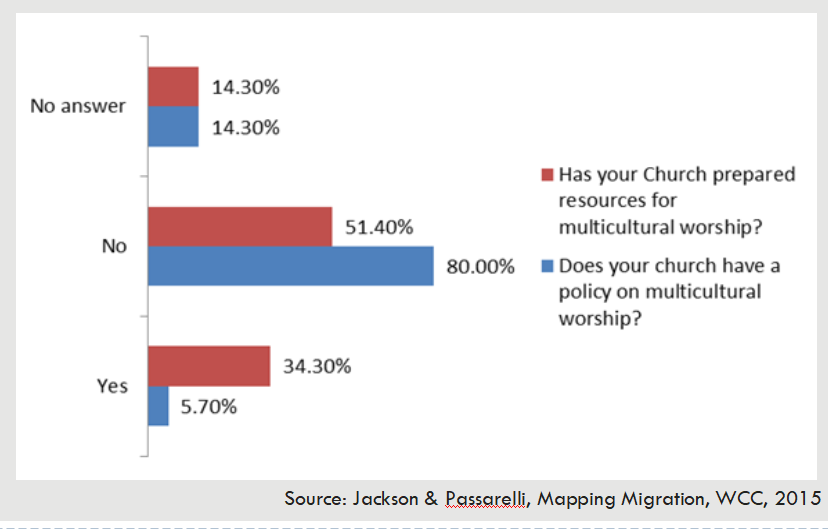

Almost half of all the churches in our survey for Mapping Migration reported that between 6% and 20% of their membership was made up of migrants (See Figure 8 above). Our research suggests that in a majority of cases, integration into the life of the congregation is unplanned and incidental. We found that the majority of churches in Europe have taken no steps to intentionally adopt policies or develop resources that take the diverse cultural background of attenders into account (See Figure below from Mapping Migration). Of course, this need not necessarily be negative but if it hinders integration, belonging, or of becoming a part of the believing church community, then clearly a higher level of intentionality is called for.

“In arriving at a theological analysis of integration, community, and belonging, we must not forget this history; for it is our history.”

By focussing our research on the integration of migrants into church communities, we have also highlighted a very obvious and frequently overlooked fact; namely that the story of migration is central to the story of the churches of Europe. Quite simply, ‘any theological account of the contemporary phenomenon of migration in Europe is not merely somebody else’s story.

The story of migration has always been internal to our own church communities and traditions; whether Protestant, Roman Catholic, Orthodox, or Pentecostal. The experience of migration has contributed to the shaping of the European Churches of today. It is a constitutive part of the narrative of the Churches in Europe; migration has always been a central aspect of the identity of the churches in Europe. In arriving at a theological analysis of integration, community, and belonging, we must not forget this history; for it is our history.’ (Jackson and Passarelli, Mapping Migration, p39).

Darrell Jackson is Senior Lecturer at Morling College, Sydney

Resourcing you:

Mapping Migration, Mapping Churches’ Responses in Europe can be downloaded as a free pdf from the website of the Churches Commission for Migrants in Europe http://www.ccme.be/downloads/publications/ or if you’d prefer a print copy, it’s available from Amazon sites in Germany, France, the UK, and the USA. Other online retailers are also stocking it.

(Mapping Migration, Mapping Churches’ Responses in Europe by Darrell Jackson and Alessia Passareli, is published by the World Council of Churches. ISBN 978-2-8254-1678-5 and is available for £11.53 or €17.65).